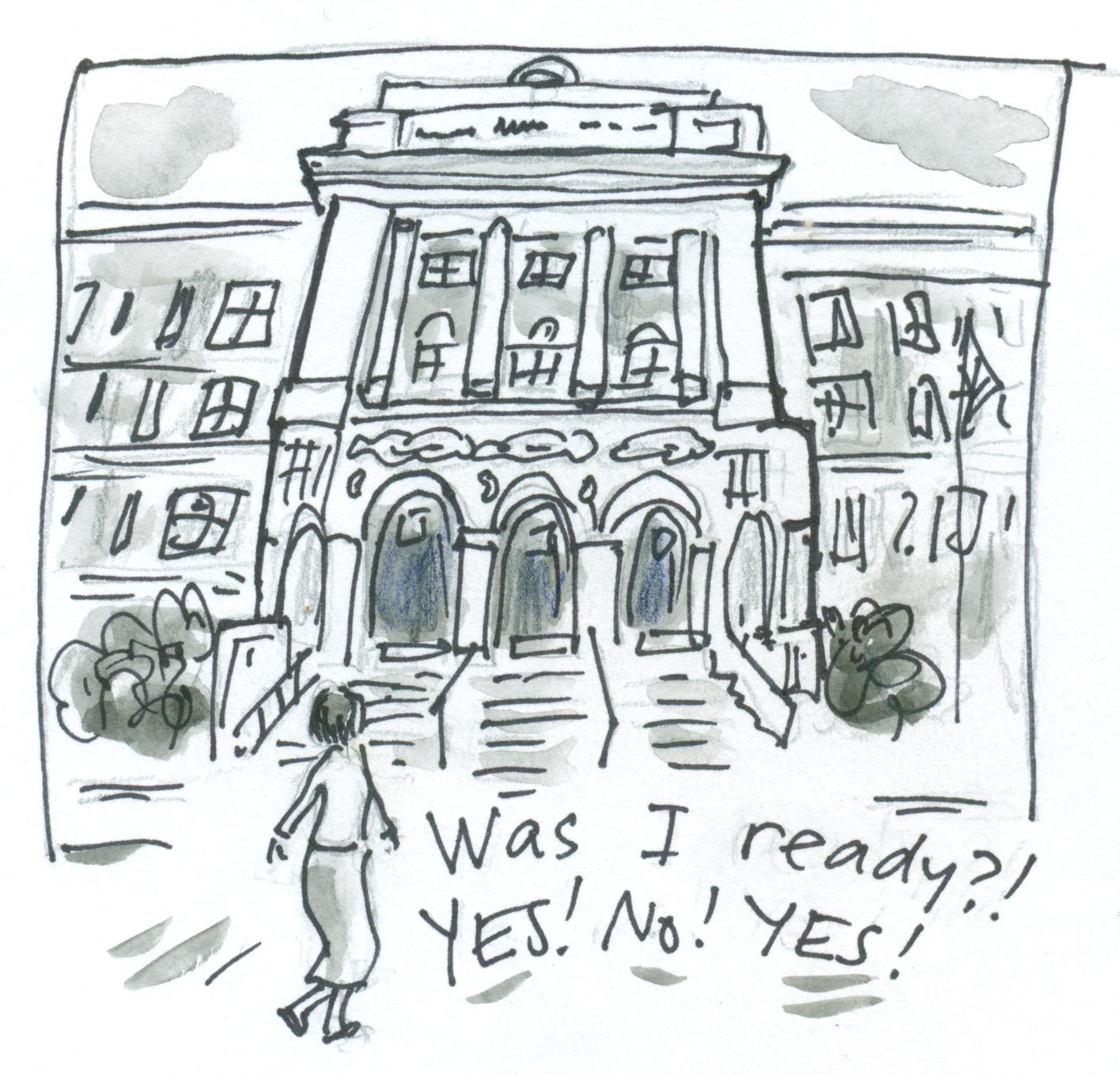

In an old high school, in a very white state, in a past so long ago it was a different country, I started a new job. It was my first “real” job as a newly certified Maine public school teacher.

I was so young that, on my first day, another teacher asked me for my hall pass.

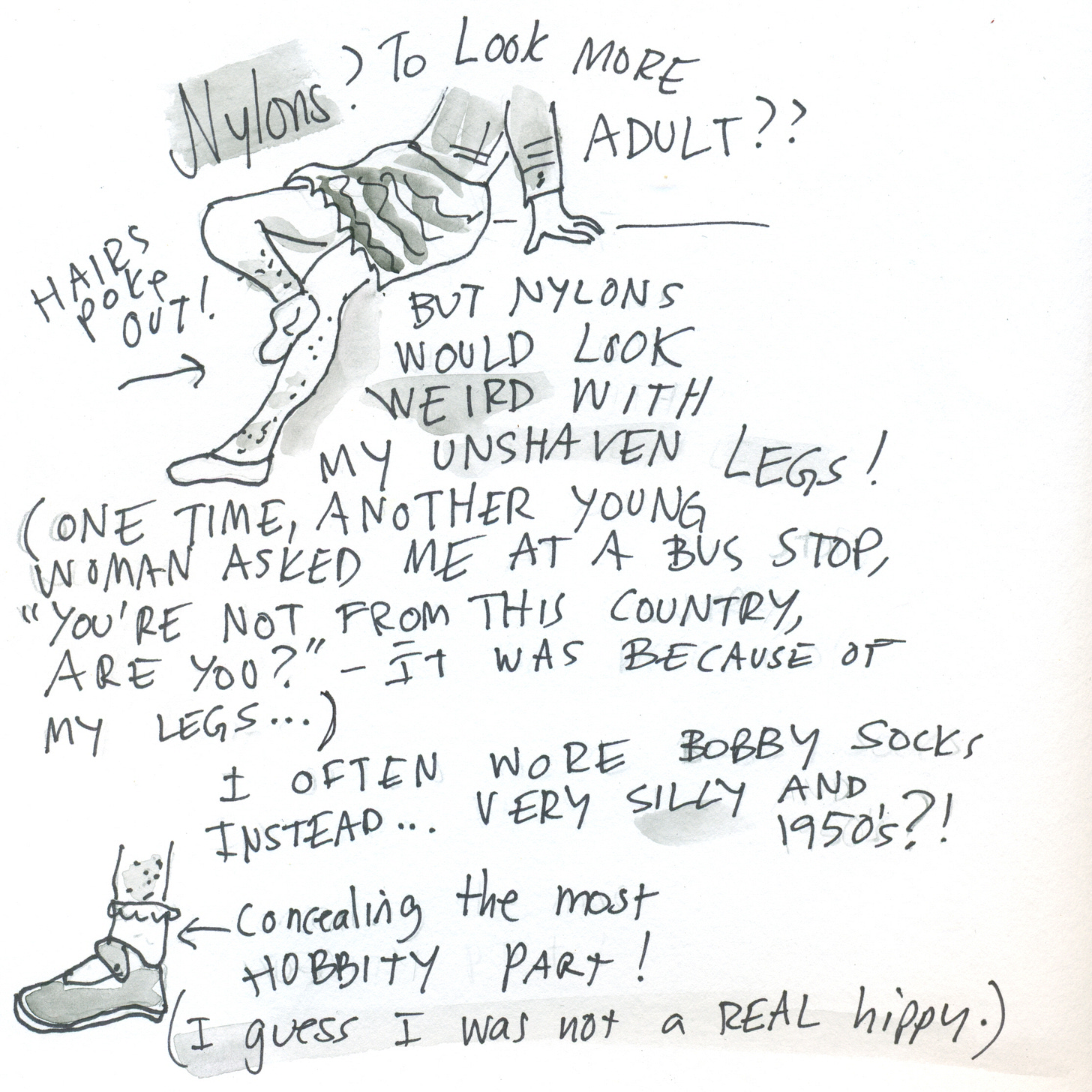

“No, I work here,” I said, wondering if I should be wearing nylons.

I was the brand new English as a second language teacher, ESL, as we used to call it, ignoring the fact that the new language was often the student's third or fourth.

English was my second language too. I remember learning it. The other teacher was Nina. She was an old seeming Russian lady. She used to call me “Little Girl.” It was a term of endearment, I think, but I hated when she did it in front of our kids. She may as well have pinched my cheeks.

Our kids were refugees. They were arriving in our city in waves, each larger than the last one. Our kids were mostly Khmer and Vietnamese, some Afghan. One guy from Poland. It was the early 80s. Eventually, Nina and I were helped by some amazing native language facilitators and one other teacher.

But in the beginning, it was just us.

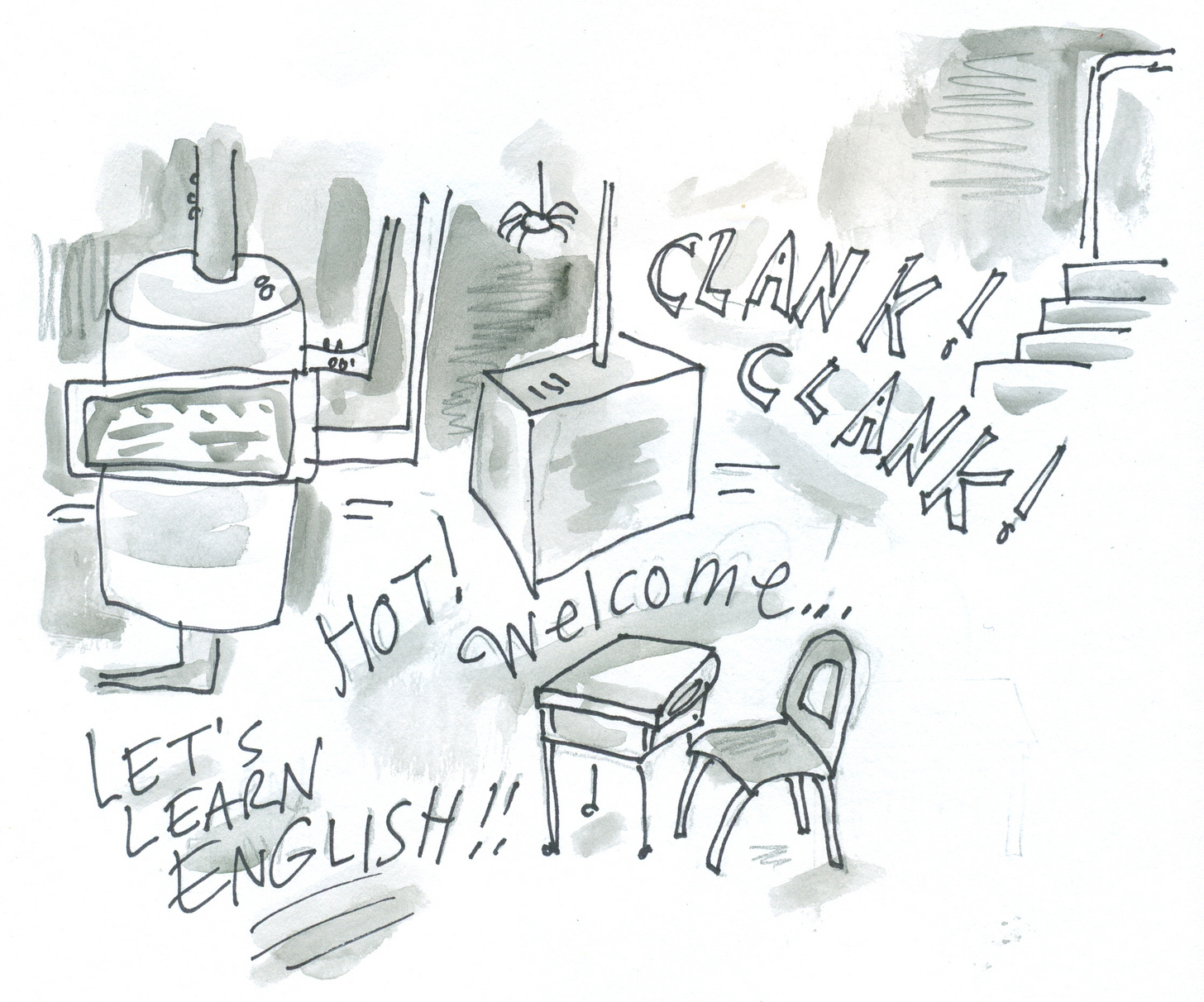

Many of these students had never really had the chance to be a student in any language, not even their own.

We didn’t have a classroom. We taught under the stairs, in the cafeteria, sometimes in a hallway or the boiler room. This was a violation of the Lau Guidelines, a Civil Rights Act from 1964. But there were no rooms to be had.

One day, the doyenne of the English department, a woman who terrified most people, pulled me aside. “Charlotte,” she said. “I feel for these children. My grandparents were immigrants from Ireland.” She volunteered to lend us her classroom for two periods a day.

The kids and I were ecstatic! Desks! Windows! Privacy! But…after just a few days, she pulled me aside again. “I’m sorry,” she explained. “I have to ask you to leave.” When I asked why, she told me in a whisper. “My students think your students … smell.”

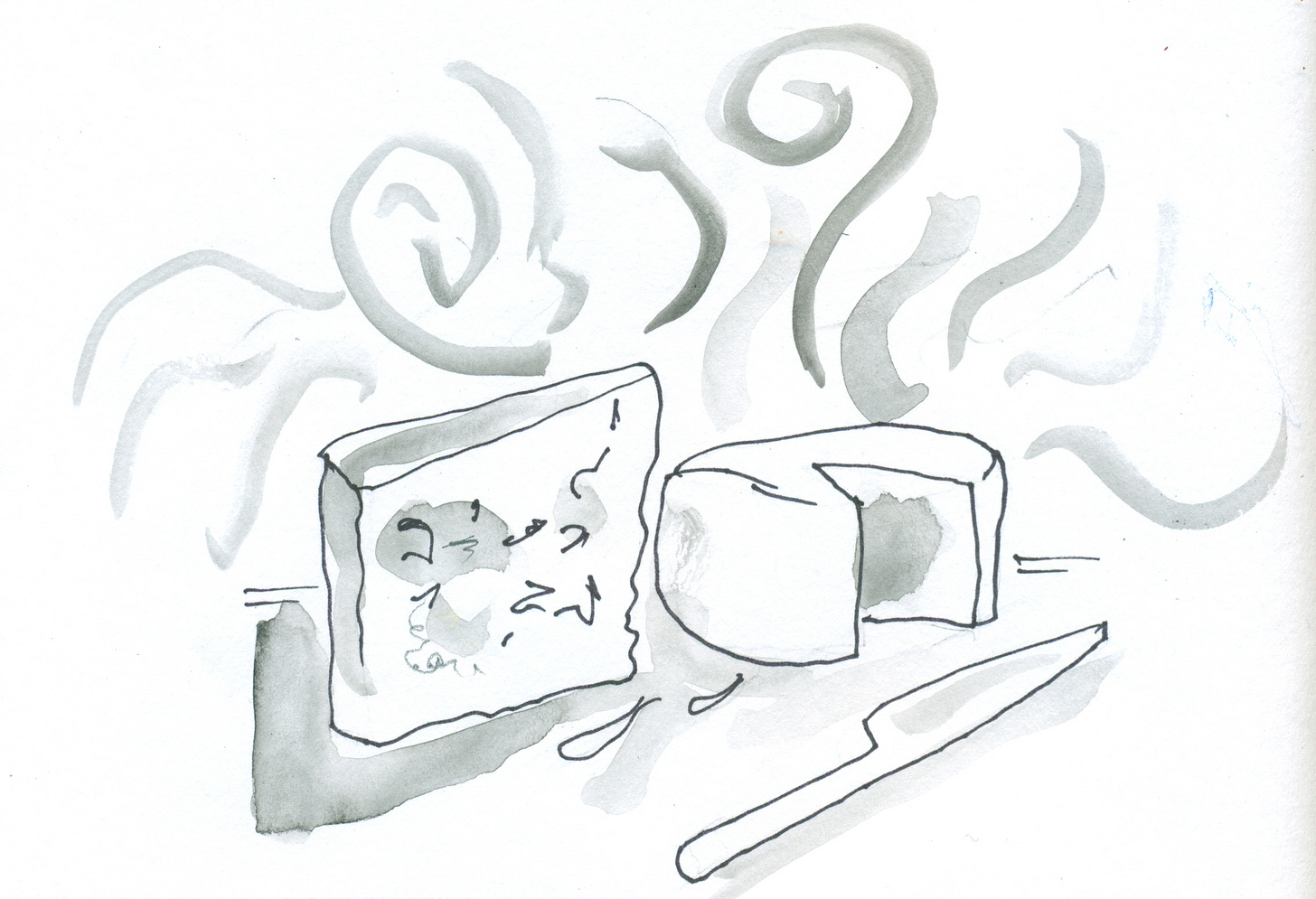

I knew it wasn’t hygiene. Despite leaving the high school to work shifts at Barber Foods, my students were showered and fashionable. It was diet. I had grown up, in part, in Hong Kong. I could smell the fish sauce and garlic of their glorious breakfasts.

But what could I say to this powerhouse of an English teacher? We moved out.

I told my kids why. I told them everything. In some funny way, I (so new to this country) identified more with them than with mainstream America, whatever that was. But their reaction surprised me. They burst into laughter, quiet laughter, then huge gulps and guffaws.

“What’s so funny?” I asked.

“You smell, too!” they told me. “Like old milk.” Ah, yes…dairy. Oozing from my pores and from most of the bodies around us. Like smelly cheese.

And so it came to me, one of the many lessons I learned from my amazing students:

WE CAN’T SMELL OURSELVES.

We went back under the stairs. Eventually, the school partitioned the library and we moved in there. This was decades ago. I am still in touch with some of these students today.

We are all Americans now.

Charlotte came to Maine from Sweden, via Hong Kong, for a liberal arts education and the 70s rock n' roll. (Who isn't searching for a heart of gold?) She's a lifelong public school teacher and the author/illustrator of many books for children and young adults. She believes that artists are emotional first responders and that art gives you questions, not answers. Which is why art is so dangerous and so necessary.

Loved this slice of life- having been "adopted" by a Vietnamese family, I appreciated this! They taught me so much.

Wonderful piece by Charlotte Agell.